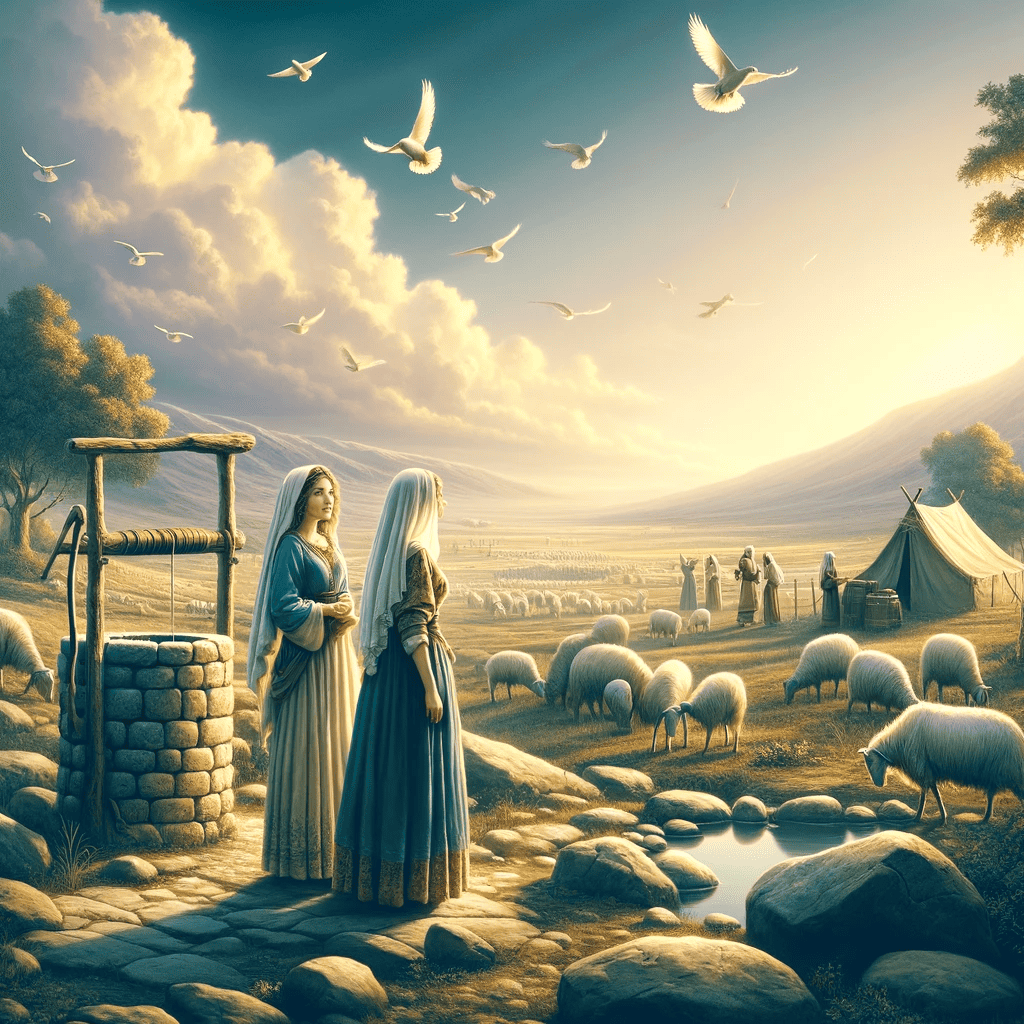

The story of Rachel and Leah is a poignant narrative of love, envy, and God’s providence, found in the Book of Genesis (29:1-30:24). It begins with Jacob’s journey to his mother’s homeland to find a wife from among his kin, as instructed by his parents, Isaac and Rebekah. Upon arriving at a well near Haran, Jacob encountered Rachel, the daughter of his uncle Laban, tending to her father’s sheep. Struck by her beauty and moved by their kinship, Jacob rolled the stone away from the well’s mouth and watered Laban’s flock. He then kissed Rachel and wept aloud in joy, for he had found his relatives.

Jacob was welcomed into Laban’s household and soon agreed to work for seven years to marry Rachel, whom he loved deeply. However, Laban deceived Jacob by substituting Leah, Rachel’s older sister, on the wedding night. In the culture of the time, it was customary for the elder daughter to marry before the younger. Jacob, realizing the deceit the next morning, confronted Laban. Laban offered Rachel to Jacob in marriage as well, on the condition that Jacob serve another seven years. Jacob accepted, marrying Rachel a week after Leah but serving Laban in total for fourteen years because of his love for Rachel.

Leah, though the first wife, was unloved compared to Rachel. God saw Leah’s plight and opened her womb, while Rachel remained barren for a time. Leah gave birth to four sons: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah, hoping each time that her husband would grow to love her. Rachel, consumed by envy at her sister’s fertility, pleaded with Jacob to give her children, to which Jacob responded in anger, pointing out that it was God who had withheld offspring from her.

In her desperation, Rachel gave Jacob her servant Bilhah as a concubine, through whom she bore two sons, Dan and Naphtali, considered Rachel’s by custom. Not to be outdone, Leah then gave Jacob her servant Zilpah, who bore two more sons, Gad and Asher. Leah herself bore two additional sons, Issachar and Zebulun, and a daughter named Dinah. Finally, God remembered Rachel, opening her womb to bear Joseph, and later Benjamin, though she died giving birth to the latter.

As the story unfolds, the intricate dynamics between Rachel, Leah, and Jacob serve not only to advance the narrative of the Israelite people but also to convey deeper spiritual and moral lessons.

Leah’s situation underscores the value of being seen by God even when overlooked by others. Despite being unloved by Jacob, Leah found favor in God’s eyes, who blessed her with children, including Judah, through whom the royal line of David and ultimately Jesus Christ would come. This aspect of the story highlights God’s sovereignty and the idea that human worth and divine blessing are not contingent upon human favor.

Rachel’s struggle with barrenness and her eventual joy at bearing Joseph and Benjamin remind readers of the theme of patience and faith in God’s timing. Rachel’s initial barrenness and later joy parallel the stories of other matriarchs in Genesis, such as Sarah, reinforcing the motif of God opening the womb in His time and for His purposes. Joseph’s birth is particularly significant, as he becomes a central figure in the Genesis narrative, leading to the Israelites’ eventual migration to Egypt.

The sibling rivalry between Leah and Rachel, while causing much personal strife, also serves to illustrate the consequences of human actions and the complexity of family relationships. Yet, through this rivalry and its outcomes, God’s plan for Israel unfolds. The sons born to Jacob, Leah, Rachel, and their handmaids become the patriarchs of the twelve tribes of Israel, each playing a unique role in the nation’s history.

The story also reflects on the practice of marriage and societal norms of the time, such as polygamy and the use of handmaids as surrogates, providing historical context and insight into the challenges and customs faced by the patriarchal families.

Moreover, Jacob’s enduring love for Rachel, despite the years of labor and deception, speaks to themes of love’s persistence and the complexities of human relationships. His willingness to work fourteen years for Rachel’s hand in marriage is often interpreted as a testament to the depth of his love and commitment, contrasting with the pain and jealousy that arise from unequal love within the family.

In conclusion, the story of Rachel and Leah is multifaceted, weaving together themes of love, envy, faith, and divine providence. It serves as a reminder of God’s presence in the midst of human imperfection and conflict, and His ability to bring about His purposes through even the most complicated family dynamics. Through this narrative, the Bible teaches lessons about human nature, the power of faith, and the importance of God’s timing, all of which resonate through the generations.