Introduction

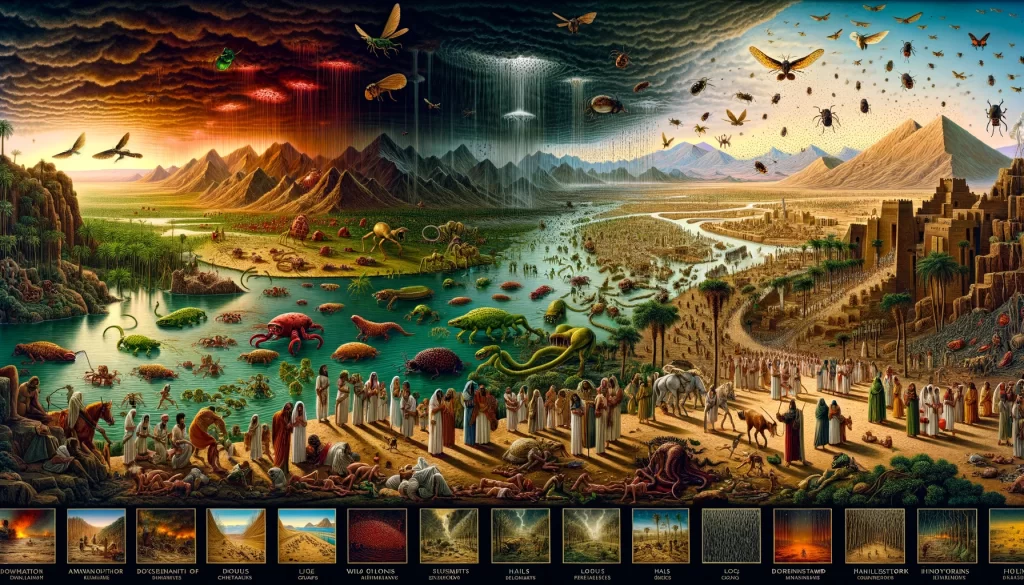

The story of the Ten Plagues, as recounted in Exodus 7-12, is one of the most dramatic and powerful narratives in the Bible. It describes the series of disasters God inflicted upon Egypt to persuade Pharaoh to release the Israelites from slavery. This narrative is not only a cornerstone of Jewish faith but also holds significance in Christian and Islamic traditions, symbolizing the struggle for freedom and the demonstration of divine power.

The Ten Plagues are a testament to the struggle between God and Pharaoh, embodying themes of justice, resilience, and liberation. Each plague serves as both a punishment for the Egyptians’ oppression of the Israelites and a demonstration of God’s supremacy over the Egyptian gods. This story has resonated through centuries, influencing religious rituals, artistic expressions, and cultural narratives around the world.

As we delve into the details of each plague, we’ll explore their descriptions in the scripture, their symbolic meanings, and the lessons they impart. This exploration will not only enhance our understanding of a pivotal biblical event but also reflect on its lasting impact on faith, culture, and history.

The First Plague: Water into Blood

The narrative of the Ten Plagues begins with a dramatic transformation that sets the tone for the divine interventions to follow. In the First Plague, God instructs Moses to warn Pharaoh that if he refuses to release the Israelites from bondage, the waters of Egypt will turn into blood. Despite the warning, Pharaoh’s heart remains hardened, and through Aaron’s staff, the Nile River—Egypt’s lifeline—along with all its canals, ponds, and even the stored water, is turned to blood (Exodus 7:14-24).

This act is not only a display of divine power but also a direct challenge to Egypt’s polytheistic beliefs, specifically targeting the god Hapi, the deity of the Nile, and symbolizing the lifeblood of Egypt’s agriculture and daily life. The transformation renders the water undrinkable, causing fish to die and a stench to fill the land, thereby crippling the Egyptian economy and disrupting the natural order.

The plague of blood serves as a stark warning of the consequences of defiance against God and sets the stage for the escalating series of plagues to come. It highlights the themes of judgment and the sovereignty of the God of Israel over the natural world and the gods of Egypt. This event forces Pharaoh and the Egyptians to confront the power of God, yet their continued resistance lays the groundwork for further divine actions aimed at securing the Israelites’ freedom.

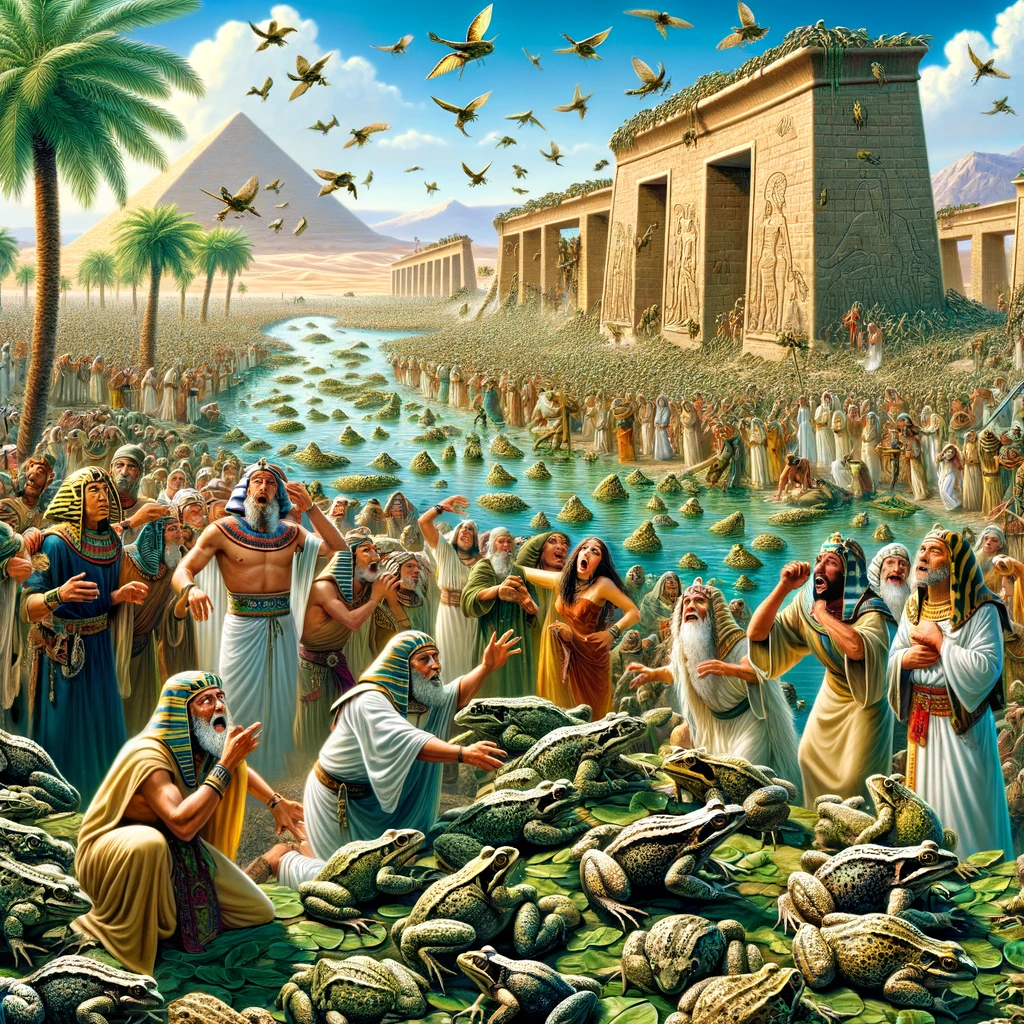

The Second Plague: Frogs

Following the initial plague, the Second Plague brought an overwhelming infestation of frogs from the Nile River, covering the Egyptian landscape (Exodus 8:1-15). God instructs Moses to command Aaron to stretch out his hand with his staff over the streams, canals, and ponds, causing frogs to swarm Egypt’s houses, bedrooms, and even into the beds and ovens of the Egyptian people. This plague was not only a physical inconvenience but also a profound psychological torment, invading the most private and sacred spaces of Egyptian life.

The frog, symbolically associated with fertility and also revered in Egyptian mythology, here becomes a symbol of chaos and disorder. The Egyptian goddess Heqet, depicted with a frog’s head and believed to protect against child mortality, is directly challenged, highlighting the contest between the Egyptian deities and the God of Israel. This plague mocks the Egyptians’ reverence for frogs, turning their symbol of life and fertility into an unbearable curse.

Pharaoh’s initial promise to let the Israelites go in exchange for relief from the frogs is quickly broken once the plague is lifted, showcasing a recurring theme of deceit and hard-heartedness. The plague of frogs emphasizes the disruptive power of God, capable of turning the natural order into chaos and penetrating the deepest sanctuaries of Egyptian life, further illustrating Pharaoh’s stubbornness and the escalating divine judgment upon Egypt.

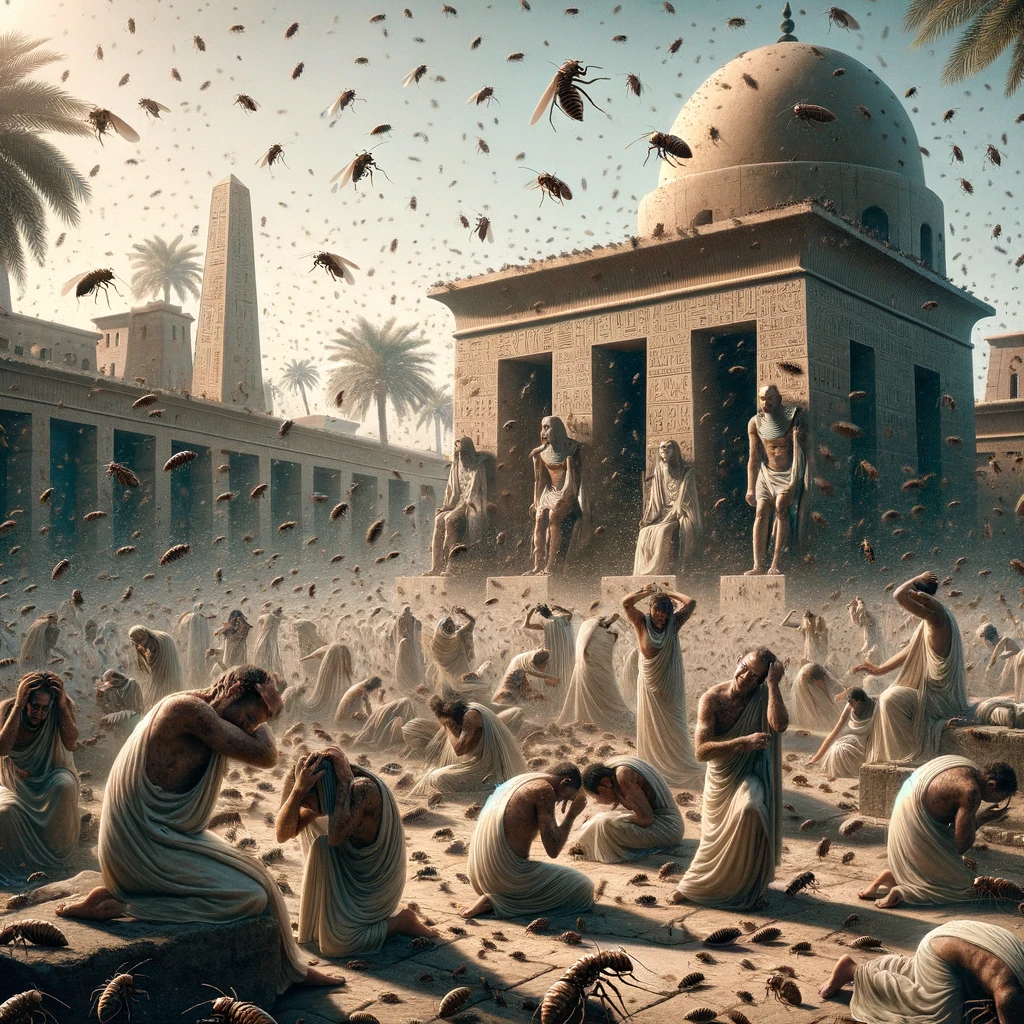

The Third Plague: Lice

In the escalation of divine judgments, the Third Plague introduced lice from the dust of the earth, afflicting humans and animals alike across Egypt (Exodus 8:16-19). This time, without warning to Pharaoh, Aaron strikes the dust of the ground with his staff, and it becomes lice, infiltrating every aspect of Egyptian life. The immediate and pervasive nature of this plague underscores a new level of divine intervention, directly impacting the physical well-being of the Egyptian people and their livestock.

Unlike the previous plagues, this one is particularly humiliating for the Egyptian magicians, who, despite their attempts, cannot replicate this feat and are forced to acknowledge, “This is the finger of God.” However, Pharaoh’s heart remains unyielded, deepening the narrative of resistance against undeniable divine power.

The lice, possibly fleas or gnats, represented not only a physical discomfort but also a spiritual defilement, rendering the Egyptians ritually unclean. This plague directly challenges the Egyptian priests’ purity, who prided themselves on cleanliness in their rituals. The omnipresence of the lice disrupts the societal and religious order, marking a profound demonstration of God’s power over the most intimate and personal aspects of life.

The Fourth Plague: Wild Animals or Flies

The Fourth Plague marks a significant shift in the nature of the divine plagues, with the invasion of either wild animals or swarms of flies, depending on the translation (Exodus 8:20-32). This plague specifically targets the open spaces of Egypt, sparing the Israelites in Goshen, demonstrating a clear distinction between the Egyptian and Israelite communities for the first time. The purposeful separation underscores God’s protection over His people, further illustrating the plagues’ selective judgment.

Moses warns Pharaoh of the impending disaster, yet once again, the warning is ignored, leading to the release of a horde of either wild animals that wreak havoc across Egypt or dense swarms of flies that infiltrate Egyptian homes and the royal palace, causing widespread distress. This plague directly challenges the Egyptian gods associated with protection and sovereignty over nature, such as Seth, the god of chaos and disorder.

Pharaoh’s response to this plague begins to show signs of concession, as he negotiates with Moses, offering to let the Israelites sacrifice to their God within Egypt. However, the negotiation is short-lived, and once the plague is lifted, Pharaoh reneges on his promise, hardening his heart once more. The Fourth Plague not only signifies God’s dominion over nature and the Egyptian deities but also begins to reveal the fractures in Pharaoh’s resolve, albeit temporarily.

The Fifth Plague: Pestilence on Livestock

The Fifth Plague introduces a devastating pestilence that strikes the livestock of Egypt, sparing those of the Israelites (Exodus 9:1-7). This targeted affliction further emphasizes the distinction between the Egyptians and the Israelites, demonstrating God’s ability to protect His people while executing judgment on Egypt.

The plague directly impacts the economic foundation of Egyptian society, affecting horses, donkeys, camels, cattle, sheep, and goats. The loss of livestock symbolizes a significant blow to Egypt’s wealth, labor force, and status, undermining the gods associated with animal fertility and health, such as Hathor, the cow goddess, and Apis, the bull deity.

In this instance, the precise fulfillment of Moses’ warning showcases the power of the God of Israel to inflict selective destruction. The distinction made between the Egyptian and Israelite animals highlights the covenantal protection over God’s chosen people, reinforcing themes of divine sovereignty and mercy.

Pharaoh’s reaction to this plague is notably different; he investigates the aftermath, confirming that the Israelites’ livestock were indeed spared. Despite this undeniable evidence of divine intervention, Pharaoh’s heart remains hardened, refusing to release the Israelites. This stubbornness not only perpetuates his people’s suffering but also sets the stage for more severe judgments to follow.

The Sixth Plague: Boils

The Sixth Plague brings an intensely personal affliction upon the Egyptians, as Moses and Aaron scatter soot from a furnace into the air, and it becomes fine dust over all of Egypt, causing painful boils to break out on humans and animals alike (Exodus 9:8-12). This act of scattering soot, a symbol of purification and judgment, directly confronts the Egyptians with their impurity and the consequences of their defiance.

The boils, a manifestation of disease and discomfort, penetrate every social class, including Pharaoh’s magicians, who are rendered powerless and unable to stand before Moses because of the boils. This signifies a complete breakdown of the Egyptian religious and magical practices, showcasing the supremacy of the God of Israel over the Egyptian deities, particularly Imhotep, the god of medicine and healing.

This plague marks a turning point in the narrative, as it is the first to directly affect the bodies of the Egyptians, making the divine judgment undeniably personal and inescapable. The physical affliction serves as a potent symbol of the corruption and decay within Egypt, a direct result of Pharaoh’s hardened heart and his refusal to heed God’s commands.

Despite the severity of this plague, Pharaoh’s response is unchanged; his heart is hardened further, demonstrating a willful blindness to the suffering of his people and the clear signs of divine power. The Sixth Plague thus deepens the narrative of judgment, highlighting the stubbornness of Pharaoh and the inevitable escalation of divine intervention.

The Seventh Plague: Hail

The Seventh Plague unleashes a catastrophic storm of hail mixed with fire upon Egypt, sparing only the land of Goshen where the Israelites reside (Exodus 9:13-35). This unprecedented meteorological event is heralded by a warning from Moses to Pharaoh, offering a chance for Egypt to shelter their servants and livestock from the impending disaster.

The hailstorm, described as being so severe that nothing like it had ever been seen in Egypt before, devastates crops, livestock, and anyone caught in the open, directly challenging the Egyptian deities associated with the sky and agriculture, such as Nut, the sky goddess, and Isis, the goddess of fertility.

This plague represents a divine display of power over nature and a direct attack on Egypt’s food supply and economic stability, further illustrating the futility of Pharaoh’s resistance against God. The selective destruction, sparing the Israelites, reinforces the notion of God’s covenantal protection and the distinction between God’s people and the Egyptians.

For the first time, Pharaoh admits to sinning against the Lord and Moses, requesting relief from the plague, signifying a temporary acknowledgment of God’s supremacy. However, once the storm ceases, Pharaoh’s heart hardens once again, retracting his confession and refusing to release the Israelites. This cycle of defiance, temporary repentance, and subsequent hardening of the heart underscores the deepening conflict and the inevitability of further divine action.

The Eighth Plague: Locusts

The Eighth Plague introduces a devastating swarm of locusts that covers Egypt, consuming what little was left of the country’s vegetation after the hailstorm (Exodus 10:1-20). This plague represents an acute attack on Egypt’s ability to sustain itself, decimating crops and further crippling the economy.

God commands Moses to stretch out his staff over Egypt, bringing the locusts as a form of judgment that obliterates the remnants of the fields, including trees and plants. The severity of this plague is such that it threatens to erase any hope of recovery for the Egyptian people, emphasizing the depth of Pharaoh’s folly in resisting God’s command.

The locusts, in biblical terms, symbolize a divine instrument of punishment and destruction, challenging the Egyptian gods associated with fertility and harvest, such as Osiris, the god of vegetation and rebirth. This plague starkly illustrates the consequences of Pharaoh’s hardened heart, not only for him but for all of Egypt, as the entire nation suffers from the king’s stubborn refusal to heed Moses’ warnings.

Despite the unprecedented devastation, Pharaoh’s response follows a now-familiar pattern: he briefly acknowledges his sin and begs for relief, only to harden his heart once the threat is removed. This recurring cycle of acknowledgment and recalcitrance highlights Pharaoh’s deep-seated pride and the tragic consequences of his refusal to submit to God’s will.

The Ninth Plague: Darkness

The Ninth Plague casts a palpable darkness over Egypt for three days, a darkness so profound that it could be felt, rendering the Egyptians unable to see one another or leave their homes (Exodus 10:21-29). This supernatural darkness, unlike any ordinary eclipse or storm, represents a direct affront to the sun god Ra, one of the most important and powerful deities in the Egyptian pantheon, who symbolized light, life, and order. The plague of darkness disrupts the very essence of Egyptian religious life, casting doubt on Ra’s power and, by extension, the authority of Pharaoh, who was considered Ra’s earthly embodiment.

This darkness, symbolic of spiritual blindness and the deepening chaos within Egypt, isolates the nation in a tangible manifestation of the judgment they face for their oppression of the Israelites. The selective nature of this plague, sparing the Israelites in Goshen, who enjoy light in their dwellings, underscores the distinction between God’s people and the Egyptians, reinforcing the theme of divine protection and segregation.

Pharaoh’s reaction to the Ninth Plague is increasingly desperate. He offers Moses a compromise, allowing the Israelites to leave but demanding they leave their livestock behind. Moses refuses, insisting on total compliance with God’s demands. Despite the severity of the plague, Pharaoh’s heart remains unyielding, leading to a final, devastating ultimatum from Moses that sets the stage for the tenth and most severe plague.

The Tenth Plague: Death of the Firstborn

The culmination of the divine judgments against Egypt is the Tenth Plague, the death of all firstborn in the land, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sits on his throne to the firstborn of the slave girl who is at her hand mill, and all the firstborn of the cattle as well (Exodus 11:1-10, 12:29-30). This final plague is not only a profound act of judgment but also a direct strike at the heart of Egyptian society and its future, symbolizing the ultimate cost of Pharaoh’s stubborn defiance against God’s command to let the Israelites go.

The plague specifically targets the firstborn, a status highly significant in ancient societies for inheritance and succession, thereby threatening the continuity and stability of Egyptian families and their social structure. It also challenges the divine status of Pharaoh, who was considered a god among his people, showing that not even he could protect his own child from the judgment of the God of Israel.

This event is preceded by the institution of the Passover, where the Israelites are commanded to mark their doorposts with the blood of a lamb, ensuring that the angel of death would pass over their homes. The Passover becomes a lasting ordinance for the Israelites, commemorating their deliverance from slavery and the sparing of their firstborn.

The impact of this plague finally breaks Pharaoh’s resistance, compelling him to release the Israelites. However, the grief and devastation left in its wake are immense, marking a turning point in the biblical narrative and the history of the Israelite people. The Tenth Plague serves as a stark reminder of the consequences of opposing divine will and the power of God to deliver His people from bondage.

The narrative of the Ten Plagues, culminating in the death of the firstborn, underscores themes of judgment, redemption, and the sovereignty of God. As we transition to discussing the theological significance and cultural impact of these events, we can reflect on their enduring legacy in religious tradition and their profound implications for understanding divine justice and mercy. Let me know if you would like to proceed with the analysis of these broader themes or if there are other aspects of the story you’d like to explore further.